The place of litter size in modern pig breeding:

A broad perspective

By Pieter Knap, PhD Genetic Strategy Manager

Context

The members of EFFAB recognise the high importance of animal welfare in sustainable pig farming. Over the past 20 years, animal breeding programs have evolved and integrated breeding goals and traits that promote animal welfare. The commitments of EFFAB members are demonstrated through Code EFABAR, the code of good practices for responsible and balanced breeding. Responsible breeding plays a crucial part in improving animal welfare.

Breeding and subsequent raising of healthy and robust animals with improved animal welfare while delivering economic returns and reduced environmental impact are all priorities for pig breeders and farmers. Animal breeding has a crucial role in providing the best animals to farmers to help them to achieve all these objectives whatever is the farming system; indoor, fully free-farrowing, outdoor or organic.

Since the early 1990s, pig farmers have had access to sows with genetic potential for larger litter sizes, which is significant due to breeding. It is well known that there is a negative relationship (negative genetic correlation) between litter size and piglet survival. This has led to the general opinion that large litter sizes are negative for Animal Welfare. Unfortunately, it is less known that selection for increased litter size can easily be accompanied by selection for improved piglet survival and it’s possible to improve these traits simultaneously. Therefore, alongside an increased ultimate number of quality weaned piglets per sow, pig breeders consider many other aspects to ensure healthier piglets at weaning and long-lived sows. This concept is called responsible and balanced breeding; initiatives like Code EFABAR by EFFAB have promoted transparency and built dialogue about balanced breeding and its contribution to modern pig farming (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Modern Pig Breeding as per Code EFABAR initiative

To be able to breed long-lived sows with larger litters, and to counterbalance the negative genetic correlation with piglet survival, pig breeders have been focusing on extended breeding goals since the early 2000s. This includes piglet survival at farrowing, at weaning and during the growing period before slaughter, an adequate number of functional teats, an adequate and homogenous birth weight, piglet vitality, and many other maternal ability traits. Selection against congenital defects, leg weakness, and negative social behavior is also part of current breeding programs (Figure 1). By combining such traits in the routine genetic evaluations that form the core of breeding programs, breeders have been able to support more welfare-friendly and sustainable pig farming regardless of the production system.

Some examples of achievements and work in progress in breeding farms

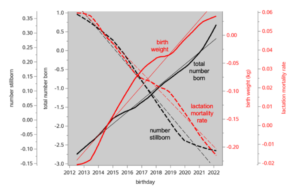

We can observe in Figure 2 that current breeding programs allow breeders to achieve a larger litter size and a higher birth weight without compromising the survival rate of the piglets at birth or during the lactation period; this disproves the notion that a larger number of piglets born will inevitably increase mortality.

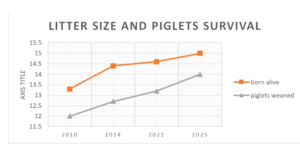

Due to the increased focus on preweaning survival, the number and quality of teats, the maternal ability of the sows, and adequate and uniform birth weight, many breeding programs achieve a stronger increase in litter size at weaning than in litter size at birth.

Figure 2 Genetic time trends of litter size (total number born), the number stillborn, the lactation mortality rate, and piglet birth weight in the PIC Camborough® parent sow from 2012 to 2022.

Figure 3 Litter size and piglet survival trends and prediction (Hypor by Hendrix Genetics)

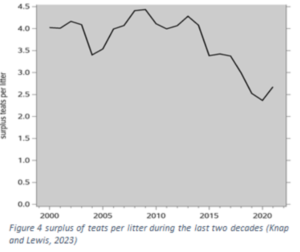

One important aspect that must come with a larger litter size is sufficient access to functional teats for the piglets to ensure that all piglets have a good potential supply of milk during the first few days of life. Figure 4 gives an example of a breeding program where up to 2014, there was a farm-wide surplus of four teats per litter (so, plenty of opportunity for cross-fostering); later on, the number of teats increased more slowly than the number of piglets born alive, so the surplus went down to 2.5 teats per litter. In 2022 the emphasis on teat number in this specific breeding goal was increased to counter that effect.

Breeders' reactivity and responsibility

Trends such as shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4 were unimaginable twenty years ago; they represent a significant advancement in pig breeding: a positive impact of genetics implementing a system approach where the interactions between animals, farmers and the production environment are fully addressed.

This article aims to show that modern pig breeding strategies, with a proper balance between the various breeding goal traits, form the successful pathway towards sustainable farming and food systems. Transparency and collaboration within the sector are critical factors in increasing awareness of the sector's reality. It also shows the responsibility of pig breeders who constantly monitor the effects of their choices. In case of negative trends, they react and adapt their breeding programs (figure 4).

Genetics is part of the available tools to improve animal health, animal welfare and sustainability. And new methods and new data will continue to contribute to improving breeding strategies to help pig farmers, in all farming systems, to adapt to future challenges.